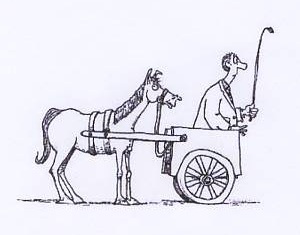

Are We Putting the Cart Before the Horse?

Are we putting the cart before the horse? Not all that long ago, a worker’s life held little value when compared to the life of a mule. In the mining industry of the early 1900s, a mule was considered to be worth more than a miner. Whenever a serious mining incident occurred, one was likely to hear “Any mules hurt?” long before hearing any concerns expressed for human life. At that time, a mule was worth $20 or $30, while workers were practically a dime a dozen. Attitudes toward worker safety have changed a great deal since those days. Now corporate board rooms from sea to sea espouse the importance of a safe workplace. Unanimously, safety is claimed to be corporate priority number one. Statistically, company after company is demonstrating lower numbers of compensation claims and reduced frequency of lost time injuries. There are even awards that can be won by companies that have succeeded in lowering lost time injury rates by 20%, 50% or more. With all of these successes, one would think work-related fatality rates in North America would have decreased significantly over the years – but they haven’t.

How can success be measured?

There are still daily newspaper and TV stories about people being killed at work. Viewers hear that a mine shaft or trench collapsed, an explosion occurred in a refinery, a worker failed to lock out an energy source, an auger caught a worker’s leg, preventive maintenance was lacking, or a design was not engineer-approved. At the same time, governments and Insurance agencies proudly proclaim that lost time injury rates have decreased and workplaces are getting safer. But when looking at the national workplace fatality rates in Canada and the United States, one can’t help but question these claims.

Between 1998 and 2008, average American workplace fatality rates decreased slightly. Had it not been for a significant drop in 2008, the 10 year period would appear on a graph as flat or rising. Nothing in the US numbers would suggest that fatality rates are trending down. Many more years of decreases would be needed before the 2008 improvement could be considered a trend, and no data yet exists to prove whether or not this is the case. Canadian fatality rates increased 30% between 1998 and 2008. Based on these statistics, neither country can boast that current approaches are improving worker health and safety. At best, the statistics suggest that a plateau has been reached. At worst, they indicate that the rates are actually increasing.

Which statistical measure is a better indication of improvement: fatality rates or the rate of lost time injuries and workers’ compensation claims? This is a delicate question to answer. Incident statistics are steeped in safety program history. However, professionals agree that an aggressive modified work program can quickly lower the rate of lost time injuries and workers’ compensation claims.

This statistical improvement doesn’t necessarily mean organizations are any safer. It may simply mean that the organization’s disability management programs have been improving and the length of time workers are away from work has been decreased. An organization’s quest to reduce accidents or achieve zero injuries can also place tremendous pressures on employees to the extent they may not report incidents and accidents. Workers may fear reporting as they do not want to be the one to spoil the perfect injury record. Therefore, it is possible to appear to have improved worker safety, at least from a statistical perspective, when in fact very little or nothing has improved at all. Fatality rates, on the other hand, can only be influenced in the long run by improved safety. If an organization has a fatality, there is absolutely nothing it can legally do to escape recording the event and including the number in its statistics. Fatality rates rates may be the most credible metric that can be used to gauge safety improvement. If this is true, fatality rates are indicating that current preventive safety approaches are not working.

Safety Excellency – Any way you slice it

Slice the pie anyway you want, it doesn’t change anything but the size and number of pieces.

If fatality statistics are suggesting that things have not improved, what needs to be done differently? The first step is accepting that current health and safety doctrines don’t always work. For 50 or more years, the health and safety profession has had one common message: implement the basic safety elements and safety excellence will be the result. Many organizations have followed this advice to the letter. Others have taken the basic elements such as incident/accident reporting and investigations, inspections and hazard identification and assessment, and divided them further into 6 or 8 or 12 or more basic safety elements. However, this rehashing process has accomplished very little, if anything at all. However one slices this safety pie, it doesn’t change anything but the size and number of pieces. One can slice the pie, dice it, blend it or do whatever one wants with it – the reality is that nothing really changes unless a change is truly made to the ingredients. In this case, proof really is in the pudding.

If safety excellence were really contingent upon merely assembling the prescribed safety pieces, many more companies would have achieved the goal of safety excellence by now. As this is not the case, more organizations are questioning the huge expenditures and tremendous attention the basic safety elements have received. Those whose livelihoods depend on the safety basics binder defend the focus and expenditure of resources, vehemently proclaiming this method to be the only way to safety salvation. Stick to the status quo, they encourage, as it is tried and true. The statistical evidence suggests otherwise.

There is a great deal more to achieving safety excellence than the basic elements found in the nicely tabulated binder bestowed by safety professionals some 50 years ago. Today, the content of the binder remains practically unchanged from the past. The content has been regurgitated and photocopied ad infinitum. And therein lies one of the biggest problems today. For too long, too many organizations have focused all of their energies and resources on the basic safety elements, only to be disappointed by the lack of safety success.

If Einstein ever caught wind of this predicament, he would leap from his grave. “That’s insane,” he would say. “Clearly it’s time to try something different.” It’s time to add some important new pages to the basic safety program binder that has guided so many organizations to legislative compliance – and safety mediocrity.

All safety excellence models are similar

Ask the companies that have achieved safety excellence and they will suggest that the basic safety element guide has omitted some essential sections (or intentionally excluded them). These additions are not cloaked in secrecy. There are many excellent models that identify additional key determinants of safety excellence. Figure 1 is an example of one of these models. What is common to these models is the emphasis they place on human factors as a key element of safety success. It is remarkable that these additional factors have been missed in the basics binder, as they really are pre-requisites. In other words, it is the human factors that determine whether or not the basic safety elements will be successfully implemented and accepted into an organization. If an organization lacks good strong leadership, if management is not deemed credible, if employee perceptions are that management cannot be trusted or if employees feel the organization doesn’t really care about them, all basic safety element initiatives will be significantly impacted in a negative way.

Figure 1 identifies the key factors or elements that consume most safety professionals’ time. These are listed under Job and Organizational Factors. Figure 1 also lists human factors that are not generally considered to be within the scope of a safety professional’s responsibilities. They are typically the job of someone else, such as Human Resources or Organizational Behaviour departments. The importance of human factors in safety excellence is not a new revelation. Many studies have recognized their importance in establishing and maintaining excellent performance. That the safety profession has not more widely recognized and applied these findings to managing health and safety is remarkable.

Figure 1

Companies that have recognized the importance of the relationship between human factors and improved safety performance have been rewarded with safety-excellent programs. Organizational behaviour research seems to suggest that the safety profession has been putting the cart before the horse. The basic safety elements have been placed higher on safety professionals’ priority lists than the framework of human factors that they actually function within.

Safety is simply good business

Is it possible for an organization to achieve safety excellence without even having a health and safety program? At the risk of a public flogging and lynching, it’s time for this writer to make a very risky admission. As a health and safety professional who has been in this business for 36 years and has assessed hundreds of company health and safety programs, one of the safest companies the author has ever worked with did not subscribe to a formal health and safety program – not one basic element. The company had procedures that incorporated safety, but it did not have safety procedures. It had staff meetings in which safety was discussed, but it did not have safety meetings. Before starting to work, the employees didn’t conduct pre-job safety assessments – they assessed their work from an operational and safety perspective. They conducted inspections on equipment and machinery, but not only for safety. For this company, safety was simply incorporated into the day-to-day activities of doing business, and excellent, safe service and products is what was provided. Ask the management of any safety-excellent company about their safety success, and they will explain that their success is based more on key human and organizational factors than on basic safety elements.

Safety-excellent companies have determined that the building blocks for safety are not contained in the basic safety element binder as it currently exists. They have come to understand that success in all areas – safety, productivity, service and quality – is dependent upon human and cultural factors such as employee satisfaction, positive employee perceptions and attitudes, management credibility and trust (see Figure 2). It’s no secret that safety-excellent companies also demonstrate excellence in all other aspects of their business. Anything that a safety professional can do to improve on the softer human and cultural factors should be viewed positively by the leadership, because the improvement will affect the entire business. This is why some companies use their safety initiatives as a springboard to improving overall corporate performance. Viewed in this light, safety activities should be perceived as adding value to the organization as opposed to a drain on resources. If an organization’s goal is only to meet basic safety requirements, it would be wise to implement a safety program comprised of traditional basic safety elements. If the goal is to achieve safety excellence, it should work on the human and/or cultural factors that are the foundation of any successful business.