YES, THERE IS A CURE FOR AUDIT PARALYSIS

As you read this, thousands of organizations around the world are busily scurrying about collecting and updating health and safety policies and procedures. They are updating employee training courses and training records, reviewing job safety analysis or hazard assessment documents, and just generally getting their companies prepared for what has become the most common health and safety management system assessment leading indicator. It’s called the “Safety Management System or Program Audit”. It goes by many other names such as the EHS Audit or Program Assessment but the processes for all of them are similar. A trained auditor or audit team, using a standard audit tool or audit protocol, assesses the health and safety management system of a company by interviewing employees, reviewing documents and conducting work site observations. Each question in the audit protocol is systematically scored and, depending on the score, the result is deemed as a pass or fail.

I am an auditor. I have been in the health and safety business for forty-three years and have spent a great deal of that time working with companies as their health and safety auditor. I am semi-retired now which has allowed me more time to reflect on ways the profession can improve. Auditing is one improvement area that I have noted. Even though I take a critical look at the audit process in this article, I want to go on record that I am a very strong proponent of the process.

As a certified auditor I spent a great deal of my time assessing company health and safety programs. Many of these companies were participating in government/safety association sponsored recognition programs. Rewards such as lower Worker’s Compensation premiums and the opportunity to bid on various jobs, were made available to participating companies that successfully passed a system audit. I used to think these programs were confined to a few parts of Canada but they are commonly used by organizations throughout North America. Without a thorough study it is impossible to know the amount of money spent to support these programs but conservatively it is in the hundreds of millions of dollars and quite possibly in the billions. With so much money invested in recognition programs aimed at improving safety, we need to make sure these programs really work to improving health and safety in every participating company. Unfortunately, this currently is not the case.

The purpose of this article is to highlight some key issues with these recognition programs and offer some suggestions as to how they can better serve their clients. The purpose is not to malign the auditor or the audit process. I am acquainted with many auditors whom I would not hesitate to recommend to any of my past or present clients and would recommend an improved audit process to anyone looking to further their health and safety management system. However, there are opportunities to improve the current audit process. It is my hope that the following information inspires more people to look at the audit process critically and work toward improving it.

Government, safety association, insurance sponsored safety system recognition programs have been in effect in some locations for as long as 40 years. Many companies have participated and benefited from these programs for that long. Specifically they have benefitted new program participants. However, the longer a company participates in the program the less likely they will continue to reap significant benefits. Here are four key program issues that should be addressed.

- First is the condition of “audit fatigue”. Audit fatigue is a condition that results when a company repeatedly conducts the same audit and the findings do not reveal new meaningful insights.

- Second is the condition of “audit paralysis”. Audit paralysis is a condition closely related to audit fatigue. Audit paralysis restrains a company from further improvement as it binds a participating company to a set of audit requirements that they already exceed.

- Third is the accuracy of the audit findings.

- Last is high audit costs

All of the above issues can lead to an unsatisfying audit results for a participating company. In order for companies to continue to benefit from the audit process, these issues need to be resolved. Here is an explanation of the issues and some suggestions on how we can address them.

Audit Fatigue

Audit fatigue is a condition many companies suffer from after auditing year after year with the same audit protocol and maybe even the same auditor. Typically these companies are mired in government/safety association program offering rewards or recognition for carrying out and passing a standard annual audit. But all too often the audit asks the same questions and every year the audit reports read the same. As companies audit year in and year out, the useful information they obtain from the approach diminishes with each passing year. (This is assuming the company acts on the findings of previous audits). After awhile, the audit results become very predictable. Audit fatigue sets in and when this happens the audit process ceases to be a good investment for the company.

What is the cure for audit fatigue? One cure for audit fatigue is to offer more challenging measurement tools. For example, safety perception surveys have been a recognized measurement alternative for over 40 years. Perception surveys can be an excellent method of gauging the success of a company’s health and safety program but for a number of reasons they have until recently proven challenging for companies to conduct.

First, safety perception surveys offered by external consultants are expensive. The do-it-yourself option is affordable but more labour intensive. Second, recognition program administrators have not established clear survey program standards in order to guide users similar to what they have done with auditing approaches. Survey questions need to be developed so that surveys can be offered to program participants. Training programs have to be developed to help companies understand how to administer surveys properly. More importantly, is that a database has to be made available so that employees can easily complete the survey, preferably on line, and survey data can be properly collected and managed. The key to the success of a survey approach, as it is with any new measurement offering, is to provide sufficient support so that it has a chance to succeed.

Stagnant Programs (Audit Paralysis) – Raising the Bar

Many companies are being audited against weak audit protocols. The audit content is primarily derived from basic health and safety elements advocated by W. H. Heinrich 86 years ago. In his book (i.e. Industrial Accident Prevention: A Scientific Approach) Heinrich proposed that key elements such as hazard identification and assessment, inspection and safety meetings are requirements for safety success. Contemporary research does not disagree with Heinrich’s elements but it also reveals that there is much more to a well-functioning health and safety management system. More recent research indicates that programs should also be assessed on other key safety determinants such as management credibility, trust, worker autonomy, work life balance, fairness and satisfaction. There is now general agreement among health and safety professionals that many of these cultural, social and psychological factors are a pre-requisite to successfully implementing the basic safety program elements.

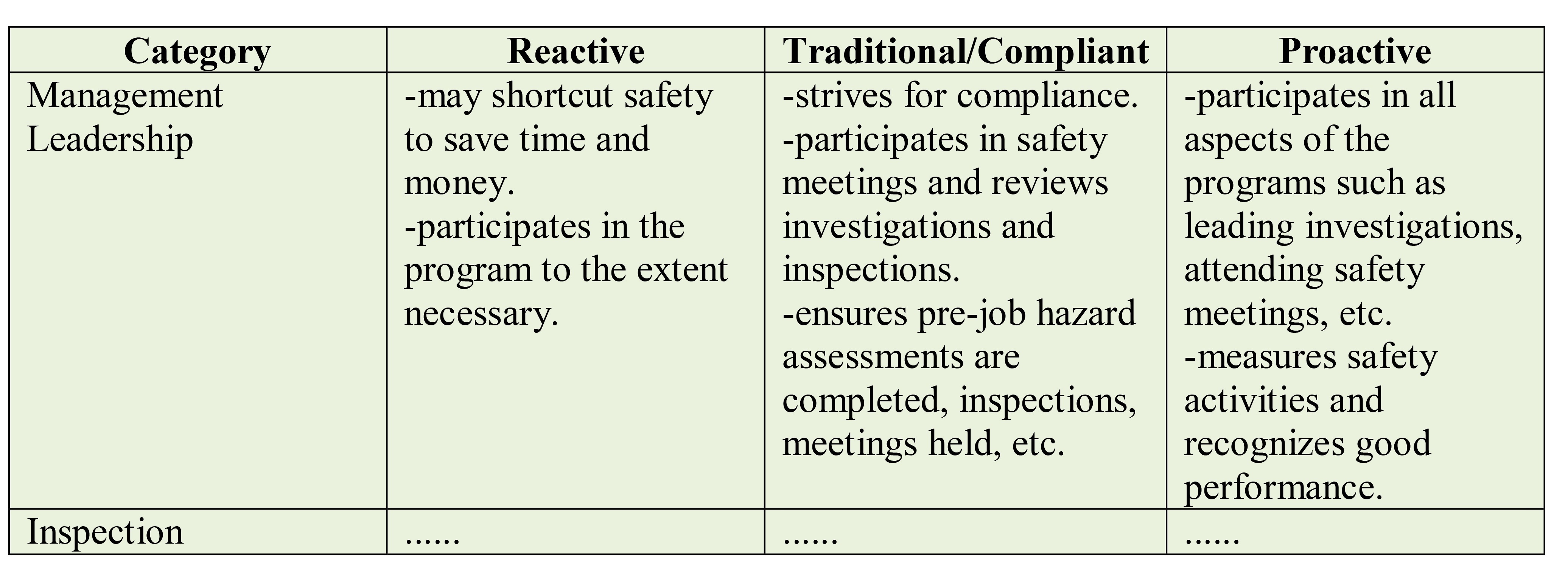

Figure #1 – Health and Safety Program Changes

Many people have been exposed to a table similar to the partial table above. The table is used to depict the evolution of a health and safety program from one that only reacts to existing health and safety issues in the Reactive column, to one that predicts and manages issues (the Proactive column). Every company program is in a different stage of development. There is no question that many companies are okay with maintaining programs in the Reactive or Traditional stage. But there are also many others that strive for more and work toward reaching World Class Safety (the Proactive stage). When all companies are measured with the same low standard, those seeking higher levels are somewhat paralyzed by the very process that promised them continuous improvement. When the certification bar is set low, more companies can succeed by passing the audit but this also provides little direction or challenge for the many companies that strive to reach a higher stage.

Most audit protocols strive only to help companies reach the Traditional stage which is essentially a compliance stage. Typically these protocols contain numerous compliance related questions such as, Are first aid regulations followed (such as the number of first aiders and first aid equipment and supplies) followed? Have hazard assessments been conducted? Are safety committee meetings being held? Are serious incidents reported to the government? System audits that focus on compliance do not assure employee safety.

What is the cure? Raise the bar. Audit protocols should focus more on benchmarking companies against the proactive steps a company takes to improve health and safety. Users and administrators of audit protocols need to stop putting Band-Aides on the more outdated audit protocols and just take them off of life support. Knowledgeable health and safety professionals should be tasked with developing new audit assessment tools that raise the bar. For government organizations and safety associations that seek to certify companies, consider a tiered certification approach. Companies whose programs are in early evolutionary stages such as the Reactive or Traditional Stage can be measured against a lower audit standard than companies at or near a Proactive Stage. Certification rewards could also be tiered appropriately to recognize companies based on their demonstrated level of effort and commitment to health and safety.

Inaccurate/Imprecise Audit Scoring

Inaccurate audit findings may understate or overstate opportunities for improvement and can cause companies to misdirect their efforts to improve. I instructed in the Occupational Health and Safety Certification program at the University of Alberta for many years. The students were either health or safety professionals seeking credentials or were students hoping to complete the program and find work in the field of health and safety. As an auditing instructor, I frequently tested the groups of students in audit workshops.

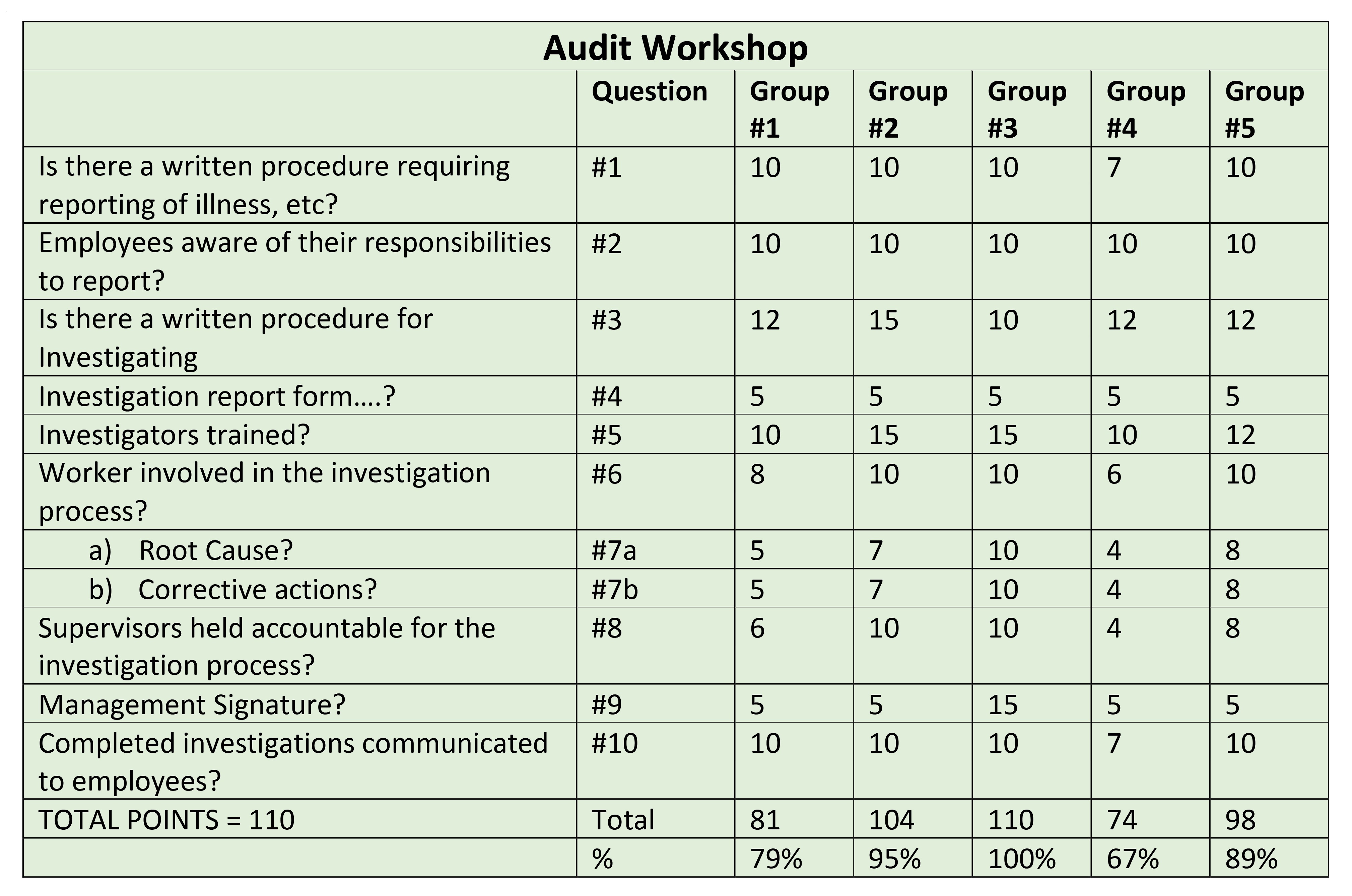

Some students, in my audit scoring workshop, indicated they had substantial experience auditing. The class was broken up into groups of four or five students. Attempts were made to separate the audit experienced students equally among the work groups. Each group was provided with the same workshop mock document, observation and interview information. From this information the groups were to score audit questions. Once completed, scores the groups’ scores were examined question by question and were posted in a table on a white board similar to that shown in Figure #2. Many of the scores for the groups were consistent. For example, if the question asked whether or not there was a particular policy or procedure in place, group scores were generally pretty close. These types of audit questions are very clear cut and easy to score. However, there were significant differences in how these groups scored other types of questions which always lead to a great deal of discussion and debate in class. For example, “Did the investigations identify root cause(s)?” Following discussion, it was determined that the groups had significant differences in their understandings of root cause(s). There were many scoring differences also noted on questions that required the groups to assess a process or a system. Scores differed because of the differences in their perception of a system.

Figure #2

What is the cure for differences in audit scoring?

- Some protocol administrators do a very poor job of specifying in their scoring instructions what auditors need to see in order to award points. The cure is simple in this case; improve the audit protocol instructions.

- To become an auditor, some audit protocol administrators require perspective auditors to have secondary education, a number of years experience managing a health and safety program and five days of training on the audit protocol. The student is then required to undergo mentorship until the new auditor is deemed competent. Other programs may certify auditors with no practical experience and only two or three days of training. It should be no surprise that these significant differences in certification requirements result in differences in auditor competency. If the purpose of the audit is to accurately assess the health and safety management system and provide direction on how to improve, we need to improve how we certify auditors. Auditor competency is a factor that accounts for significant differences in audit scoring. If the audit process is to maintain credibility as a leading measurement indicator, the auditor competency bar has to be raised.

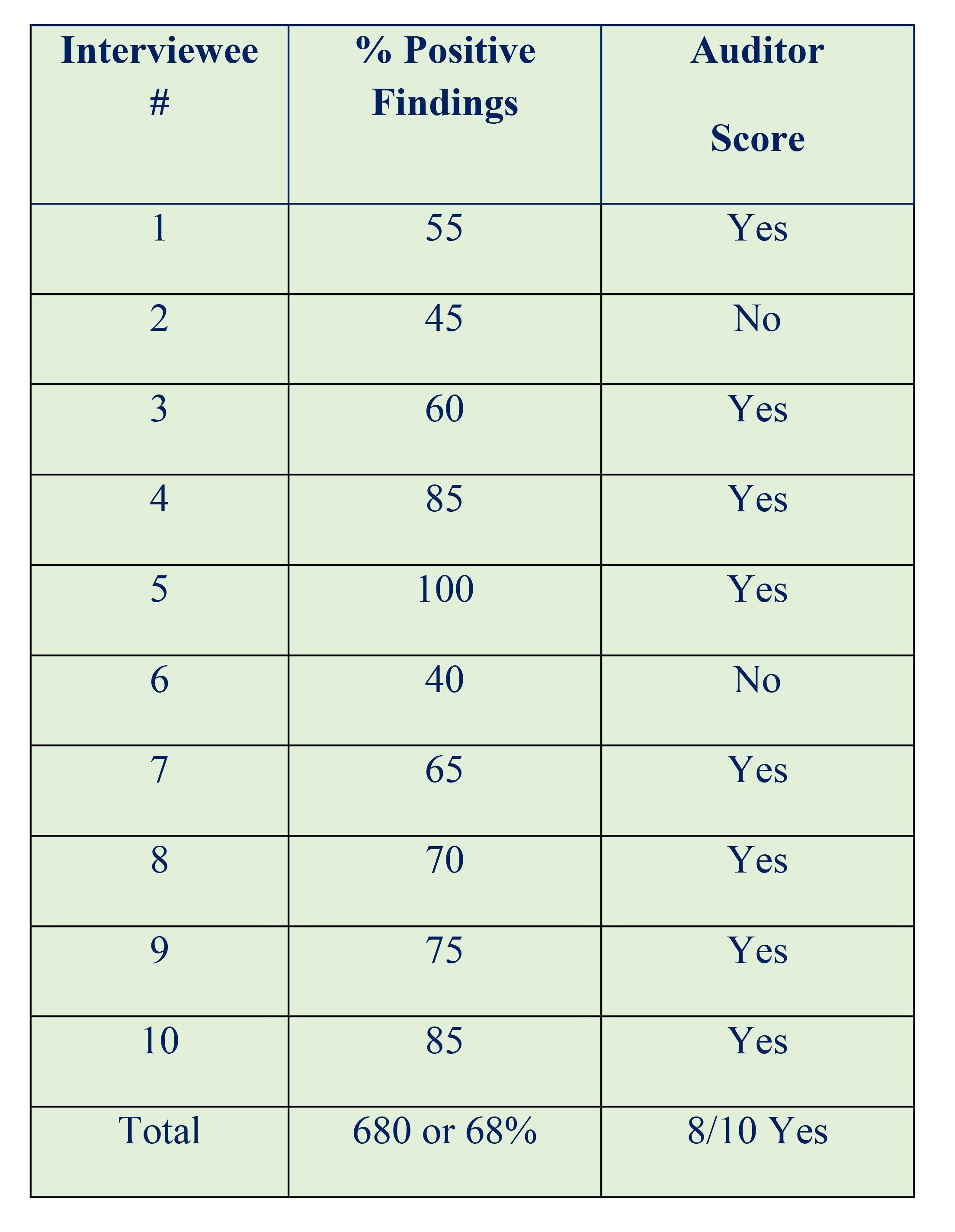

The way audit questions are scored can also result in inaccuracies. Typically audit protocols utilize a combination of two types of scoring, All or None and Range Scoring. With all-or-none scoring, the auditor basically has only two scoring choices (besides undecided). There is a NO response or a YES response. The audit protocol instructions generally outline at what percent positive point and auditor is to select the YES or NO score. For example, let’s assume that auditors are to assign a YES to any percent positive response above 50% positive. In an interview the auditor must determine to what extent the interviewees response is positive or negative. If the interviewee is unsure the auditor must probe deeper to determine if the response is 51% positive or greater for a YES (i.e. 100% positive score) or less for a NO (i.e. 0% positive score). Assuming the interviewee’s response is just over 50% positive, the question is scored as 100% positive or YES. This method of scoring is very imprecise and the confidence in the score decreases with each subsequent interview. Figure #3 depicts the two scoring options of All-or-None scoring.

Figure #3 – All or None Scoring

For each All-or-None interview score, one is left wondering to what extent employee responses were actually 0% or 100% positive and to what extent they were somewhere in between. Let’s examine the scoring more closely using the auditor’s percent positive findings for each of the ten interviewee response shown in Figure #4. In the middle column employee responses are shown in terms of percent positive. The score necessitated by the audit protocol is shown in the Auditor Score column as the score must be either YES or NO.

Figure #4 – All or None Scoring

Figure #5 – Range Scoring

Once all of the interviews are completed, the auditor adds up the YES scores and the NO scores and comes to a conclusion on scoring the All or None points for that question. In this case, because eight of ten interviews score positively, ten out of ten, or full points would be awarded for the question. The issue with this scoring is that full points are awarded based on 68% positive responses. In fact, full points would have been awarded had the percent positive indicators been 51%. Some audit protocols attempt to mitigate this issue by instructing auditors to not award full points unless the positive indicators are higher such as 60% or 70% positive. This doesn’t solve the scoring issue but does improve it. If you are expecting your audit results to accurately reflect the state of your health and safety management system, you need to be aware of the number of All or None scoring questions in the audit protocol and the percent positive indicators required to obtain full points. There are significant consequences to companies that fail an audit as they may lose their ability to bid on projects because they cannot meet audit certification requirements. How they are scored could be a deciding factor.

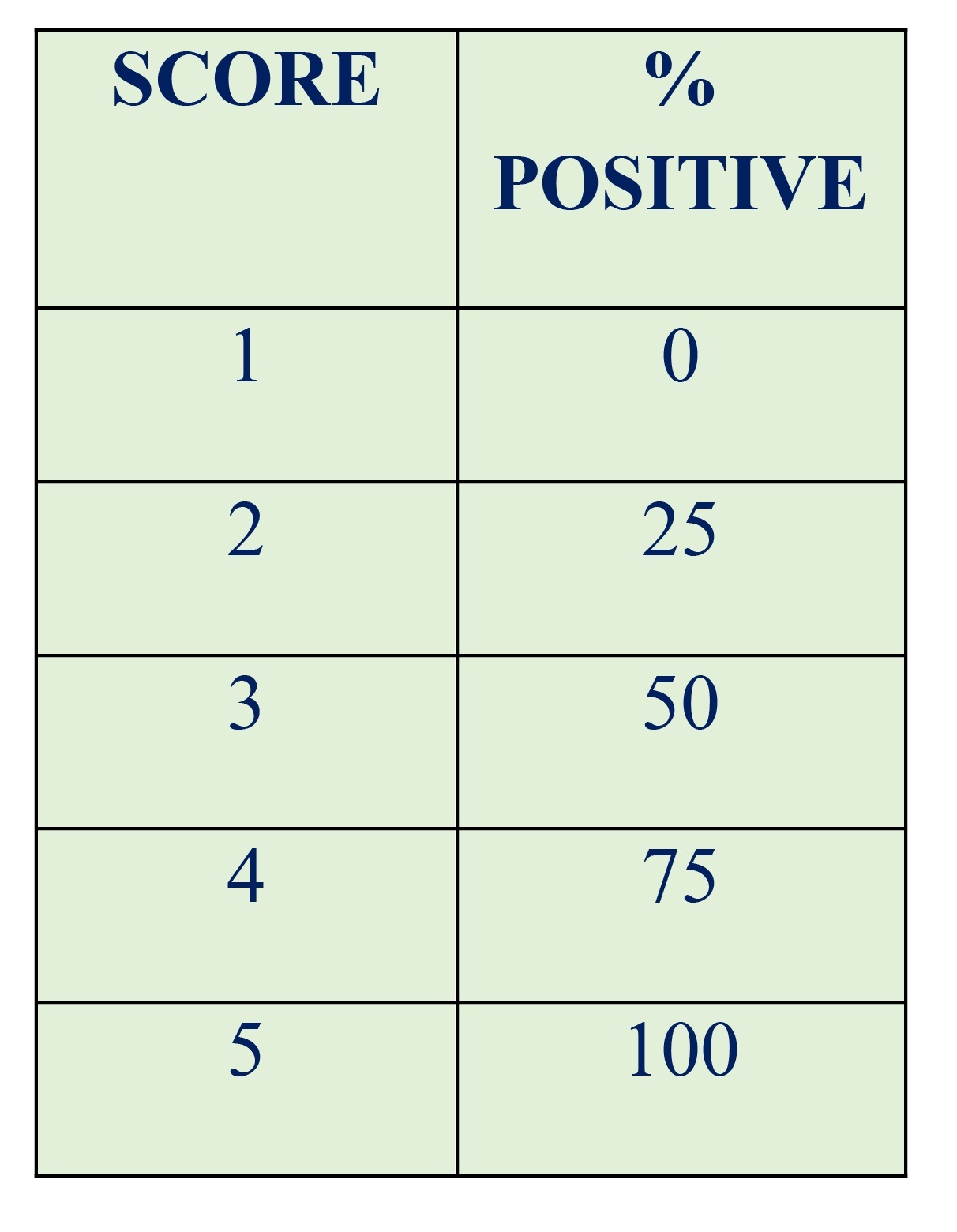

The cure for this scoring problem may be to use range scoring where the auditor or respondent may select a percent for 0 – 100 or select from scores on a scale as shown in Figure #5. Either scoring approach provides companies with a closer estimated score of each question (e.g. 1- 5 scale where 1=0%, 2=25%, 3=50%, 4=75%, 5=100%).

High Audit Cost

Throughout the world, there are programs administered by governments and safety associations that certify companies that have passed a basic audit protocol. Certification often promises incentives for companies to participate such as lower compensation insurance premiums or the ability to meet the pre-requisites needed to bid on contracts. The ultimate goal of these programs is to see one hundred percent of the company membership participate in the program. Unfortunately, this goal may not be realistic given the high upfront costs associated with auditing. For smaller struggling companies the upfront costs needed to participate in annual audits are just too high. If the audit process were less costly, more companies would be able to participate.

Is there is a cure for high audit costs? One way to cut audit costs is to reduce the high cost associated with gathering audit information. The audit process requires certified auditors to review documents, conduct observations and interview employees. Generally, the highest cost in the audit process is in conducting employee interviews. Each interview is typically 30 minutes to 1 hour in duration. If there are 50 interviews to conduct, it may take the auditor four or five days to conduct them. Time needed to conduct interviews may represent 75% of the auditors on site time and 50% of the total time needed to complete all audit requirements including writing the report. Some audit administrators have attempted to make the process more affordable by allowing auditors to collect interview information using a limited number of worker surveys (excluding supervisor or management). However, without a database to collect and manage all of the survey interview response data, little time is saved because auditors still need (and charge for) the time to review each of the completed respondent surveys and then consolidates all of the findings. In this case, the survey option offers little real cost savings if the option is not supported by a database capable of managing interview data.

What is the cure? The cure is to provide auditors with a proper web based survey database. The database should be capable of collecting employees’ scores and comments for each audit question and also have the ability to manage and sort through all of the data (e.g. by position, location, department, etc.). When it is made possible to have all workers complete the surveys electronically, auditor costs can be cut in half as a good web-based database allows employees to complete the audit surveys anytime and anywhere, and can then consolidate all of the respondent data. This approach to soliciting employee perceptions is cost effective and it removes the auditor who could unintentionally bias responses. The reduced audit costs would be appreciated by all certificate participating companies and it would open the door for many more employers to participate in the audit process.

Conclusion

The issues discussed here all have an impact on the value the audit brings to each participating company. Audit fatigue stifles the improvement efforts of companies that have outgrown the audit protocol. Alternative measurement options need to be offered and supported. Audit paralysis hinders improvement. Participants’ health and safety programs become stagnant and improvement is discouraged by the low bar set by unchallenging and outdated assessment tools. A tiered participation approach would allow companies to achieve certification at an appropriate stage of program development. Changes to the audit protocols are necessary in order to improve accuracy of audits-changes to content and types of scoring as well as consistency in auditor certification requirements. These changes will ensure audit findings do a better job of correctly providing direction for improvement. A great deal more can be done to explore more affordable ways to conduct audits and safety perception surveys as well. It is ironic that the measurement approaches that we currently advocate to improve health and safety can be so helpful for some companies yet so limiting for others.

All of the issues presented here can be readily resolved. Employers and safety professionals need to demand improved and alternative measurement systems. The systems need to be credible, flexible and affordable. They need to challenge all employers to continue to improve and not paralyze them by setting the bar too low. Employers need to demand a good return on their program assessment requirements just as they would require on other aspects of their business. Current research is telling us that there is much more to health and safety success than the basic elements advocated by W. H. Heinrich 86 years ago. It is time to act upon current research and provide participating companies with measurement approaches that challenge them and yield more opportunities for continuous improvement.